Mixed-race couples speak about their romances. Their love lives tell the tension and abuse that are surprisingly still present in these modern times.

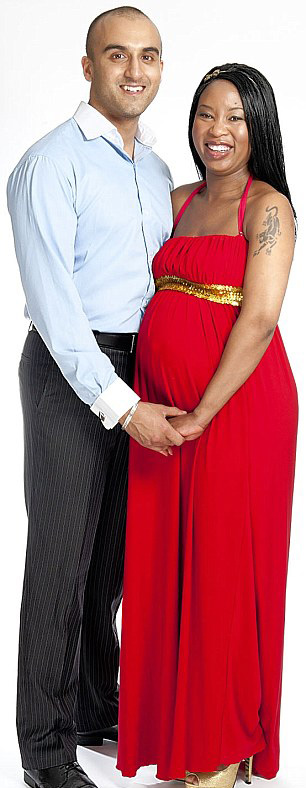

“It caused real problems with his family.” | Primrose Kaur and Jaspreet Singh, 2009

Primrose Kaur, 32, is married to Jaspreet Singh, 27, and they are expecting their first child. The couple works as civil servants, and they live in Windsor. Jaz is a Punjabi Sikh born in Britain and Primrose is a black Zimbabwean brought up in the UK.

Overcome disapproval: the couple said that they have to be strong to stand by their decision to marry each other.

Told by Primrose: When I was 12, my parents sent me to the UK to live with my sister, who is much older than me. They thought I would get a better education in the UK, and I was sent to a Catholic grammar school.

After college, I began working for an airline authority, which is where I met Jaz. We fell in love, but it caused a lot of problems with his family. My family were fine about me marrying a Sikh—we are already a mix as my father is half-Chinese—but the Indian view remains that people should not marry outside their culture. Actually, immigrants who have not been in Britain long are accepting, it’s the longer established communities that are less open to change. And it’s very unusual to see couples who are black and Asian. In the Asian community, if a man marries a white girl, it is just about acceptable, but a black girl? No way. The cultures just aren’t used to mixing.

People have a view that Britain is a highly accepting multicultural society, but there are prejudices that still exist among certain races and religions. What’s surprised me most is actually how few differences there are between Jaz and my outlook. He was actually sent to India for three weeks to meet prospective brides agreed by his parents while he was dating me. They didn’t realize how serious we were, but by then we were in love; and when he came home, he told his mother that it was me he wanted to marry.

We married in 2009 and had a white wedding at a register office and then a traditional wedding at a Sikh temple in Southall. My mother couldn’t come over because of the problems in Zimbabwe, but both his parents attended. I haven’t converted, as Jaz is not particularly religious, but I think he will encourage our children to go to a Sikh school where they can learn Punjabi. I support this. Because my heritage is already mixed, I don’t really have a cultural identity, and I think it would be nice for our children to have a stronger sense of where they come from.

Told by Jaz: It was very difficult for me to pluck up the courage to tell my family that I wanted to marry a black African girl.

In my culture, there’s a lot of pressure to marry a girl of the same culture and also caste. A lot of parents disown their children if they make a marriage like this. My parents’ view was that they wanted me to be happy, but my extended family was concerned. It really took strength to stand by our decision. We will aim to bring our children up within both faiths: Sikh and Christian.

I actually think it is much more important that they are good people, rather than if they are Sikh or Christian. There are far too many problems in the world caused by people who are overly religious.

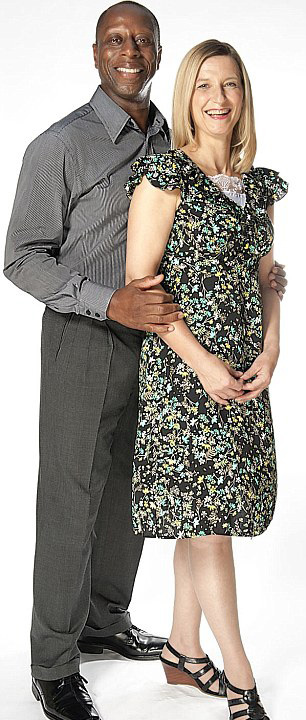

“I was spat at as I pushed our baby’s pram.” | Jan and Tony Lloyd, 1990s

Tony, 54, is a son of immigrants from Jamaica. Tony runs a martial arts fitness company, Fighting Fit. He is married to a white English woman named Jan, 54. The couple has a 10-year-old daughter named Toni.

Told by Jan: Tony and I got together after I went to one of his fitness classes. It was the mid-nineties, not long after Stephen Lawrence had been murdered in South London, and a time when tensions were high between the black community and the police.

One incident in particular brought it home to me how different life could be for Tony, compared to the white boyfriends I’d had. He was driving home from work in his Mercedes one afternoon when he was stopped by police investigating an armed robbery.

Despite the fact his car was emblazoned with his company logo, and he was wearing his martial arts uniform, they hauled him out at gunpoint before thoroughly searching both him and the car. When he told me what happened, I was incredibly shocked. He said he got the impression that if he made any unexpected move, they would have shot him. That sort of thing just wasn’t something I’d ever encountered before.

When Tony and I married in 1996, I was the first person in my family to marry a man who wasn’t white. Mine was a very traditional middle-class background—my family are Home Counties’ farmers, and I was privately educated. They were very polite to Tony, but my parents worried about how our children would cope with a mixed identity. This was unchartered territory for them.

But even now, it still shocks me how much, often unspoken, racism remains in Britain. When our daughter Toni was just a baby and I was pushing her through the park in her buggy, an elderly man, whom I knew by sight, came over. I thought he wanted to coo over the baby, but he spat at me. It left me shaking.

Tony and I sometimes don’t get asked to certain events in the community where we live, and while nothing is ever said, the only difference is that we are a mixed-race couple. But thankfully, Toni is oblivious. She attends a multi-racial church school, and I don’t think she ever considers the color of her skin. My parents had nothing to worry about. Hopefully, by the time she’s old enough to marry, the issues we’ve faced really will be a thing of the past.

Told by Tony: When I got together with Jan, the fact that she was white wasn’t an issue for me—I had been out with girls from different backgrounds before. I was simply attracted to her personality and the fact that, like me, she loved keeping fit.

But mixed relationships can be difficult for some elements of the black community to accept. While this isn’t why I fell for Jan, some black women think that a successful black man only wants a white wife as a status symbol and that it means black women are somehow not good enough. But then you hear of black women who only go out with successful white men, so sometimes black men are treated as inferior too. My parents came to Britain in their late ‘20s, as part of the Windrush generation of Jamaicans who were encouraged to come and settle in the UK.

Thankfully, like the rest of my family and friends, they have always been very accepting of Jan and relationships like ours.

[dfp1]

“People shouted ‘paki’ on the street.” | Pamela and Shafique Uddin, 1960s

Pamela, 63, is and English woman married to Shafique, 75, a retired restaurant manager. Shafique is from Bangladesh. The couple lives in Stepney, East London. They are proud parents of six grown-up children, three boys and three girls, and nine grandchildren.

Told by Pamela: It was Shafique’s amazing mop of jet-black hair that first attracted me to him. I was 14, and I can still remember seeing him in the kitchen of the local Wimpy restaurant where he was the chef.

The next time I went in, he served me, and we got chatting. Nearly fifty years on we are still together. My family lived near Brick Lane, in East London, and the Fifties and Sixties were a time of great change there. A lot of Bengali men came to London to find jobs, like Shafique, and many moved to Brick Lane, which has since become a strong Bangladeshi community.

A lot of my friends were attracted to the Asian men. They were smart, nice-looking, well-dressed, and well-spoken. When Shafique and I started going out, my mother was fine, but my dad was horrified. He refused to come when we married in a register office in 1965, when I was 19. He thought Shafique wouldn’t stick by me, but once we’d been married a few years and he saw how my husband looked after me, he admitted he had been wrong and Shafique became his favourite son-in-law.

Some people living in our area were hostile. They shouted, ‘‘Paki’’ at Shafique when we walked down the street, and lots of nasty things were said to us.

Our first date was to an Asian cinema to see a love story. I did get a lot of looks, though they were more surprised than anything else. We now have a home in Bangladesh, and I am always treated like a queen when we visit. After we married, I converted to Islam, and we decided to bring up our children as Muslims, so there were never any disputes between us at home. However, we have always celebrated Christmas as well as Eid, and our children, and now grandchildren, love it because it means they get a lot of presents.

Told by Shafique: Sadly, my mother never met my wife—she died before I could take Pamela back to Bangladesh. But I know she wasn’t happy about my marrying a non-Muslim girl.

My children nearly all have multicultural marriages, and we are very happy about that—one son has married a Turkish girl, another a Jewish girl, one daughter a mixed-race man, and another an Englishman. We have no prejudices; everyone is welcome in our family.

“My father threw me out of the house.” | Mary and Jake Jacobs, 1940s

Mary, 81, is married to Jake, 86, and they have no children. The couple lives in Solihull in the West Midlands. Mary is a former deputy teacher while Jake is a retired post office worker. Jake is originally from Trinidad.

Told by Mary: When I told my father I was going to marry Jake, he said, ‘‘If you marry that man, you will never set foot in this house again.’’

He was horrified that I could contemplate marrying a black man, and I soon learned that most people felt the same way. The first years of our marriage living in Birmingham were hell—I cried every day and barely ate. No one would speak to us. We couldn’t find anywhere to live because no one would rent to a black man, and we had no money.

People would point at us in the street. Then I gave birth to a stillborn son at eight months. It wasn’t related to the stress I was under, but it broke my heart, and we never had any more children.

Now it’s very hard to comprehend the prejudice we encountered, but you have to remember that there were hardly any black people in Britain in the Forties. I met Jake when he came over during the war from Trinidad, as part of the American forces stationed at the Burtonwood base near my home in Lancashire. We were at the same technical college. I was having typing and shorthand lessons, and he’d been sent there for training by the Air Force. He was with a group of black friends, and they called my friend and me over to talk. We didn’t even know they spoke English, but Jake and I got chatting. He quoted Shakespeare to me, which I loved.

A few weeks later, we went for a picnic but were spotted by a lady cycling past—two English girls with a group of black men was very shocking—and she reported me to my father, who banned me from seeing him again.

Jake returned to Trinidad, but we carried on writing to each other; and a few years later, he returned to the UK to get better-paid work. He asked me to marry him, quite out of the blue, when I was only 19. My father threw me out, and I left with only one small suitcase to my name. No family came to our register office wedding in 1948. But gradually, life became easier. I got teaching jobs, ending up as a deputy head teacher. First Jake worked in a factory, then for the Post Office.

Slowly, we made friends together, but it was so hard. I used to say to new friends, ‘‘Look, I have to tell you this before I invite you to my home—my husband is black.’’ My father died when I was 30, and although we were reconciled by then, he never did approve of Jake.

Today we have been married for sixty-three years and are still very much in love. I do not regret marrying him for an instant, despite all the pain we have suffered.

Told by Jake: I feel so fortunate to have met and married Mary, but it saddens me that we could not be accepted by society. Nowadays I say to young black people, ‘‘You have no idea what it used to be like.’’

When I arrived in the UK, I was subjected to abuse every day. Once I was on a bus and a man rubbed his hands on my neck and said, ‘‘I wanted to see if the dirt would come off.’’

And back then you couldn’t work in an office—because a black man in an office with all the white girls wasn’t thought to be safe.

These stories, painful as they sound, prove one thing: love sees no race. After all, people do not fall in love because of one’s skin color; they love their partners as who they are, regardless of what culture they came from.